Classic Cars

At the moment, I am living a life without classic cars. Turned to guitars and amplifiers instead. Except that… I am still a frantic watcher of TV programs like Fantomworks, Wheeler Dealers and Chasing Classic Cars! They allow you to sit back, enjoy the sights and sounds of fantastic vintage vehicles and learn a bit about the technology, whilst calmly sipping a cold beer on the couch.

Restoration or Modification?

“Restomod” is a word that pops up quite regularly in those TV shows. Obviously, it’s a contraction of the words “Restoration” and “Modification”. Hmmm, but wait, there’s a contradiction in there; if you restore something properly, you are by definition not going to modify it. You are just not adding another sunflower to a Van Gogh painting, when you’re restoring it, or another figure to Rembrandt’s famous Night Watch. So, when a customer tells Dan Short, the owner of Fantomworks garage, that they want their classic car to become a restomod, I always find it a bit of a pity (not that the people at Fantomworks are not doing a great job!). Originality will be sacrificed for performance and comfort, a rare vintage engine with a lot of history and character may be swapped for a brand-new LS.

Then, a couple of weeks ago, my old Gibson Hercules amplifier inadvertently caught my eye… and I was quite shocked to realize that, OMG, over the last couple of years, it has gradually turned into a restomod! How come? Hold my beer.

Another Gibson

After first having restored and sold a 1967 Gibson GA-5 Skylark, I was looking for another vintage Gibson amp, but one with a little bit more power and a bigger speaker. The Skylark (18W) was already reasonably powerful, but its combo package with 10” speaker just didn’t cut it. I ended up importing a 1962 Gibson GA-60 Hercules, with a 15” speaker and some 35 Watts of power from two 7591 power tubes… awesome!

Turning the engine

When you first fire up a vintage amp, you never know exactly what’s going to happen. Will there be noise or hum, flames, sparks, will the circuit breakers pop? Luckily, the Hercules didn’t do any of that. It remained pristinely calm and when a plugged-in guitar was strummed, things sounded as they should, basically. The amp produced some decidedly vintage tones, albeit without sparkle or enthusiasm. A faint fuzz sound could also be heard in the background when playing chords… could become a nightmare to find out where that came from!

More about the amp

With just volume, bass and treble controls and no reverb or tremolo effects, the Hercules seems a rather inconspicuous amp. Under its hood, it has some features that set it apart from many other tube amps of the 1960s however: two not-so-common 7591 output tubes, a rather unique optical compression circuit and a post-phase inverter gain stage. Was it meant as an answer to Fender’s Pro-Amp, with its 15 inch speaker? In any case, the Hercules was quite a powerful amp for its era, so it makes perfect sense that a piggyback (top and cabinet) version of the GA-60 was sold as the Gibson GA-100 Bass Amp.

“Space Savers”

“Space Savers”, that is what Vacuum Tube Valley magazine called those 7591 tubes in their September 2004 (20th) issue. A duet of 7591s, run right at their limits, was claimed to produce some 45 Watts of power; quite a punch for small, 6V6 sized bottle! The 7591 was an example of Westinghouse’s relative invisibility as a major vacuum tube manufacturer. Introduced in 1958, the 7591 has hardly been written about in any vintage electronic publication. Yet, it was one of the most popular high-fidelity tubes ever made. Millions of stereo receivers and hifi amps produced by Fisher, Scott, Harman-Kardon, McIntosh, Sherwood, Pilot, Sansui, Kenwood, Pioneer and other manufacturers must have been equipped with them. Intended solely for entertainment purposes, they were also used in many Ampeg guitar amps and some Epiphone and Kalamazoo models. Gibson installed them in their Duo-Medalist “A”, Super Medalist, GA-30RVT Invader, GA-40T Les Paul, GA-60 Hercules and GA-100 Bass Amp models. Its overdrive characteristics are often praised and described as “somewhere between a 6V6 and a 6L6”.

A duet of 7591s, run right at their limits in push-pull mode was claimed to produce some 45 Watts of power. Photo © Sander de Vries, 2020.

A handy sidekick that packs a punch?

Back to the exterior of the GA-60, where brown tolex and ditto-colored speaker grille give it what we might now consider a funky vintage look. With its light-weight cabinet and chassis, plenty of power and cool Gibson-logo, the amp seems a portable and eye-catching sidekick to bring to jam sessions and gigs. That is, if you dig clean tones or bring your own overdrive pedals and reverb… because even with maxed-out volume, the amp didn’t show the slightest sign of overdrive. It didn’t nearly have the volume expected from a 30W amp either, let alone 45W… Disconnecting that built-in compression circuit, something that Hercules owners allegedly have been doing since the 1960s, didn’t yield much of a power-boost much either.

Resto…

Although it was probably designed to stay clean at all times, chances are that the amp wasn’t meant to sound that tame. The best way to know how it would have sounded when it was new, would be to replace all potentially worn-out parts with new and similar components. In the case of this Gibson, it meant installing two new 6EU7 preamp tubes (a low-noise equivalent of the 12AX7), two 7591 power tubes and, for safety, a new GZ34 rectifier as well. Said types of tubes appeared to be quite rare and pricey these days (except the GZ34), but at least they are still being produced, by Tung Sol in Russia for instance. The electrolytic capacitors, particularly the filter capacitors, should probably also be changed and perhaps even the speaker.

The original tubes of the GA-60 and their new equivalents. After having verified that the old tubes were still perfectly fine, they were put back. Interesting (for a Dutchman) to see that Gibson used Philips GZ34/5AR4 rectifiers, made in Holland.

The tubes were thus temporarily exchanged for new ones and the old capacitors were replaced , re-using the old drill holes to attached the new can capacitors wherever possible. The amp certainly sounded better after that, but the annoying background buzz stayed… the old tubes were absolutely fine in comparison with the new ones however and the original speaker proved to be the culprit. Removed from the cabinet, a 10-inch-long crack in its brittle paper cone became visible. From a reader and fellow owner of vintage Gibson amps (thanks DS!), I learned that this speaker was a Fisher (EIA code 1056, manufactured 41st week of 1962 (241), model number S6065). Speaks for itself that it should be left in place, right?

The original Fisher S6065 speaker had a big crack in it.

Now, here’s a dilemma for the conscientious vintage amp tinkerer… the amp just sounded so much better through a modern Eminence Legend speaker! It was like removing years of grease, dust and smoke from an old Rembrandt. Suddenly, much more treble and bass became audible, instead of the boxy (and buzzy) sound of the Fisher. What to do? Replacing the speaker is an entirely reversible operation, at least if you keep the original speaker. Quickly enough, the Eminence was installed in the Gibson and the Fisher went to the storage department, waiting for its cone to be repaired with speaker glue one day.

Over time, I found that the Hercules still didn’t have enough treble and dynamics for my taste. That opinion was shared by a befriended Fender Rhodes player, who tested the amp in a gig, as a more portable replacement for his Fender Twin Reverb. It was just a bit flat and lifeless, and what’s the point of having a cool vintage amp if it doesn’t sound cool? And that sentence is intended to justify our first steps on the sliding slope of restomods…

… Mod!

The only likely cause for the lack of treble that I could think of was the original tonestack, a funky vintage design, with just treble and bass controls and rather limited response. Replacing it with a James tonestack, with a wide range of response and low insertion loss, might be the solution. You can build one on the back of two potmeters, with the advantage of not needing any additional tags or attachment to the chassis. In the case of the Hercules, however, the controls are so far apart that this wasn’t a very practical option; the legs of the components are simply too short to bridge the distances between the potmeters!

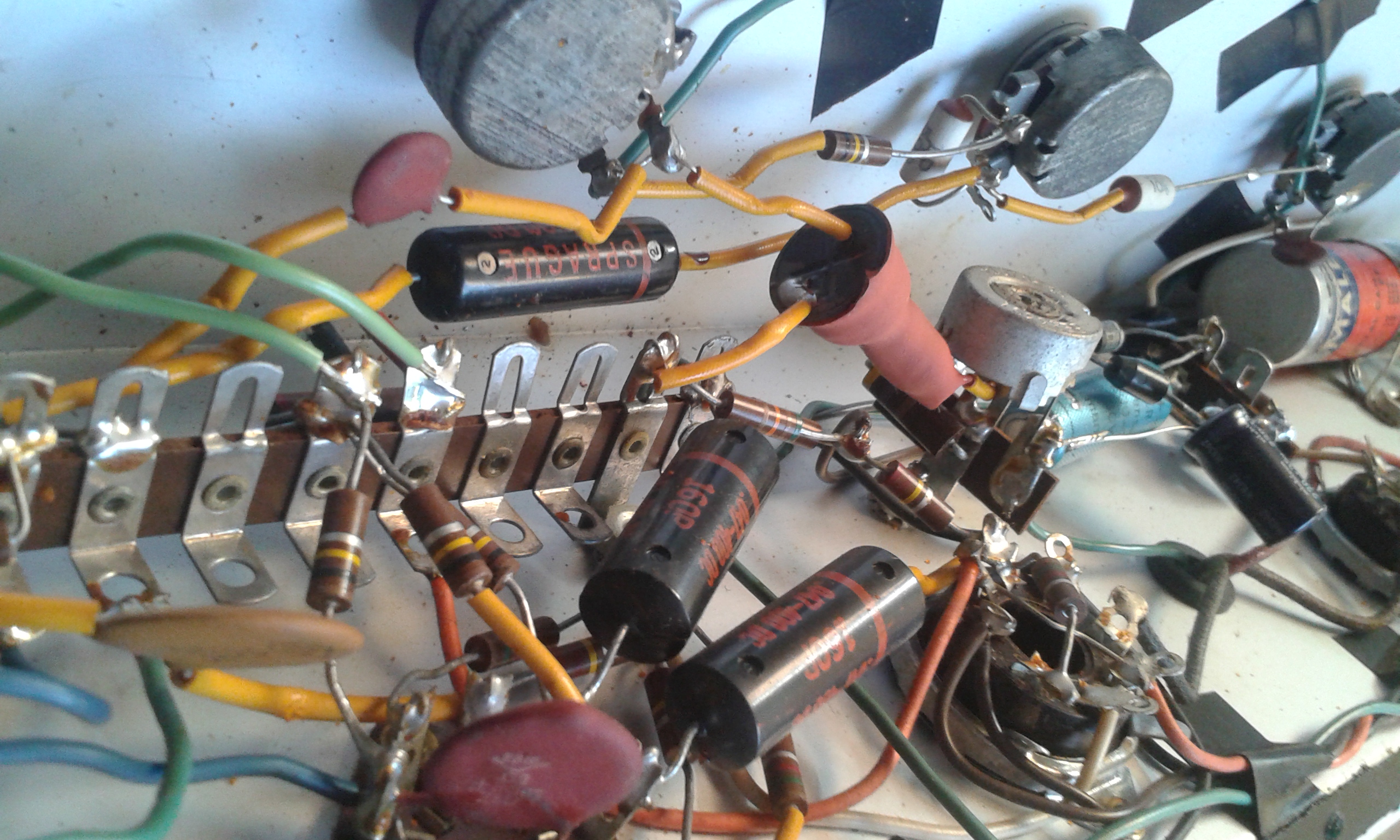

The solution was to entirely remove the built-in optical compression circuit and lay out a James tonestack on the soldering tags that would be freed in that way… un undeniable and irreversible deviation from the original design of the amp. A treble bypass capacitor was also added to the volume control. To compensate for the somewhat higher insertion loss of the new tonestack, the cathode of V1 was bypassed with a new capacitor, to create a bit more gain… and that’s another deviation from the original. Or is it? Interestingly, the GA-100 Bass Amp had a cathode bypass cap, which makes it feels slightly less inappropriate at least.

The Hercules’ built-in compression circuit is visible in the right-hand-side of the picture. It is comprised of a LDR/lamp assembly (red/pink, funnel shaped with yellow leads), a trimpot, and a couple of diodes and electrolytic capacitors. It was replaced in favor of a James tonestack.

Noise

Hearing the sonic changes brought about by all that soldering was quite delightful at first: indeed, the amp had more sparkle and it was also driving those output tubes harder than before, resulting in a whopping increase in volume! There was one setback though. The amp had suddenly become quite noisy, to the extent that it really amazed me. Was all that noise now becoming audible because of the expanded treble range of the amp? I couldn’t believe it, but decided to strategically replace a couple of carbon resistors with equivalents of the quieter metal film type, namely the cathode and plate resistors of V1 and a large drop-down resistor. The results were hardly spectacular, unfortunately, and the issue kept bugging me for quite some time. What had I done to that precious Gibson amp…? Then, a bright idea: I swapped the two 6EU7 tubes in V1 and V2. Problem solved! Apparently one of the triodes was a bit less than perfect and, without knowing it, I had placed it in V1 position, which is the most sensitive to noise!

The new Tung Sol replacement 6EU7 preamp tubes were quieter than the vintage (RCA?) originals, but one of them had a bad triode, which caused a lot hum. The problem was solved by simply swapping V1 and V2. Also notice that funky brown tolex!

Conclusion

With the noise problem solved, I am quite happy with the amp, except that, ahem… it could perhaps use a bit more bass. I’m suspecting that the output transformer is the limiting factor here however and for sure, that tranny is not going to be replaced. Reason for that hypothesis is that, in the meantime, I have also designed and built a entirely new 7591-based amp (soon more about that!). With a similar tonestack and power amp, but bigger transformers, that amp has a lot more bass on tap. For now, my conclusion is that I have managed to turn an otherwise not-so-great amplifier into something that is a lot more usable and joyous to play… which may well prevent it from ending up in the scrap heap for year to come!